Part 4 Philip K Dick 1971 Interview

James Holmes: Over the years, how has your attitude towards your work changed?

Philip K. Dick: It hasn’t changed at all.

James Holmes: Well, has your confidence in your writing changed?

Philip K. Dick: I never had any.

James Holmes: You never had?

Philip K. Dick: Just tenacity. Inability to know when to give up, and a constant rejoicing that I didn’t have to give up as quickly as I thought I would have to. By not knowing how to give up, I was able to keep on going when any sane person would have knuckled under. This was especially true in the beginning. Like before I sold my first story, people said, “You can’t sell a story. Only professionals can sell stories.” Then, after I sold my first one, they said, “That was terrible. You’ll never sell another.” Then, after I sold a whole bunch, they said, “You prolific hack writers just write the same story over and over again,” and so forth, you know, and they were always right, but I just, you know, never paid attention, and I went right on writing.

James Holmes: From what I’ve been able to read, people have been amazed at your versatility. You seem to write– You have your stories in practically every kind of magazine and the stories seem to fit the magazine. Do you do that intentionally?

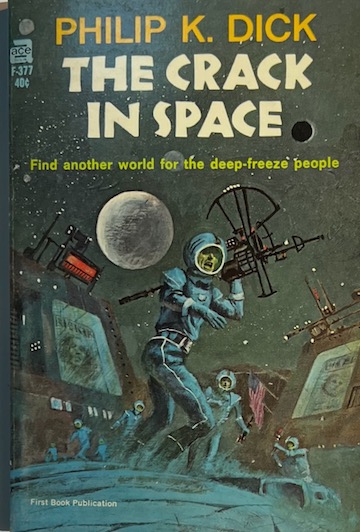

Philip K. Dick: No. I don’t write for any market at all. Well, I don’t write stories really any much anymore, I write novels now, but, that has always been true that my stuff seems to– When it comes out in a magazine, it looks like it was written for the magazine. I mean, it seems to be that kind of story, but I mean, I used to write them, you know, and I’d send them off. It was sort of a kind of an idiot savant thing on my part. Like, I would write– When I was writing a lot of stories, like I wrote a story every other week for three years, and I would write a really crummy, rotten, lousy story, and I would look at it and I’d say, “That’s perfection, man,” and I’d send it off and it would be snapped up by Planet Stories or Thrilling Stories or Startling Stories, or something like that, and when it would come out, it would look just like it was written for them. Then, the next week I’d write another thing that was what they call a quality story, and I’d say, “Man, that’s perfection,” and I’d send it off and it would get picked up by Fantasy and Science Fiction, which had fairly high literary standards, and it would come out and it would look like I wrote it for them, and I never could tell the difference when I wrote it. When I wrote something, I couldn’t tell if it was any good or not. I’d make it as good as I could and it would vary from really awful to fairly good. The shorter it was, the better it was. I noticed later that the longer the story, the worse– and I wrote some awful stuff in good faith. I mean, I never sent off anything that I knowingly, you know, that was knowingly bad. I mean, I never said– Like I’ve had colleagues say, “Well, this is no good, but I’m gonna send it off anyway,” or “It could be better, but I don’t have the time,” or “they don’t pay enough so it’s not worth improving.” I’d sit there and improve the God damn thing and really work it over until it was, and I’d work all night and on and on and on, and then I’d say, “This is perfection, man,” and it could be very good or it could be very bad, and I never knew the difference until later. Other people knew the difference right away, but there was always a market. That was the creepy thing. Every story that I wrote, I sold, and every science fiction novel that I’ve written, I’ve sold. There has always been a market for it. It’s like I have written with markets in mind, a variegated selection, you know quite a range of markets, and I haven’t at all. It’s really weird, really freaky. The only thing where that screwed up was I started writing stories when the magazines went out of business; like, there were 16 science fiction magazines at one point, and then the next week there were two, and I didn’t know the difference. I kept right on, you know, a story every other week, and then somebody pointed out there were no longer any magazines down at the newsstand, you know, so I wrote my agent. I said, “You know, how come there are no magazines on the newsstands anymore?” It’s because they all went out of business, Chester. Didn’t you notice?” And, also the word rate dropped from seven cents a word to a half a cent a word. You now get $400 for a whole novel, which was exactly true, $400 for, you know–

James Holmes: When was that? Is that now?

Philip K. Dick: No, thank God. That was back in the old days.

James Holmes: Right. When

Philip K. Dick: That was back about 1957; 57 to 59, at which point, I stopped writing magazine-like stuff entirely because the word rate having gone down to half a cent a word, you literally couldn’t make a living no matter how much you wrote at a half cent a word. You couldn’t write enough words to make a living.

James Holmes: And, that’s when you started heavy into novels?

Philip K. Dick: Well, I had already started writing novels because I foresaw something of that kind, that is, I calculated how much you made from the average novel. See, stories, when you sell a story to a magazine, you are paid on a per word basis. Like, they have a fixed rate, like two cents a word, three cents a word, and you know when you send off the story exactly how much you’re gonna get if it sells to a particular magazine. Well, I calculated the length of an average novel, which is 55,000 to 60,000 words, and the average per word rate at that—it came out to much higher than the magazine average per word rate, so–

James Holmes: At that time?

Philip K. Dick: So, I shifted over. Yeah, it came out to about five to six cents a word compared to about two to three cents, so I started writing novels as a kind of insurance policy against the future, you know, that is that ultimately I figured it would pay off better to write a novel. The only thing was, that was like, you know, as I said, about 1954 and 1955 that I started writing novels, and you probably don’t remember back in those days. That was before automobiles were invented and they still used shells, you know, and brightstones for money, but there were no good novels being published. Maybe there were three or four good novels in almost a decade.

James Holmes: Science fiction novels?

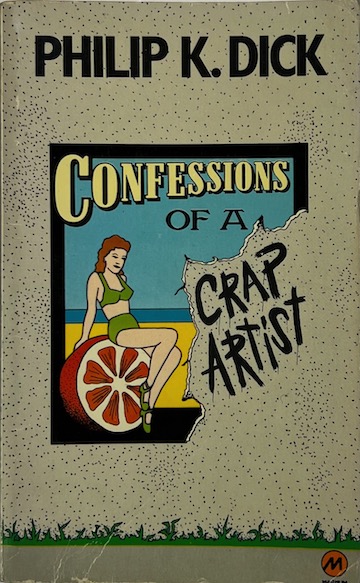

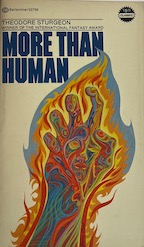

Philip K. Dick: Science fiction, yeah. Sturgeon– Well, like More Than Human, a couple of Bradbury, Pohl and Kornbluth book collaborations, and that was about all; just a few over that long period of time, and most of the writers in the field were very good in story writing, like Robert Sheckley was a good example; he had tried to make the transition to novel writing and hadn’t been able to do it. Even Bradbury, to some extent, was having a great deal of difficulty making the transition, and I’m not sure that he ever really did make a successful transition. Just about everybody, and there were a lot of very good story writers out, Sheckley was a prime example, simply could not make that transition, and in trying to make it, just faded out of the field, just simply disappeared and never came back, and I decided that before I switched over to novel writing, I would make sure that I could do it– that is, you know, I would not send off a bunch of inept novels and fail as a novel writer, because if I fail as a novel writer, there was no place to go in fiction as I construed it, because, to me, the novel was the ultimate

form of fiction, and if I screwed that up– I mean, I could screw up short story writing and go to the novel as a natural evolution anyway, you know, but what would I do if I couldn’t do a novel? This is really what has ruined a couple of very fine writers who did make the transition, but not successfully; lost their ability really as a writer and continued to write novels anyway, and so disappeared. So, when I sent off Solar Lottery, I had already written eleven novels that I never sent off. That was my twelfth novel that I sent off, and that had been worked over and studied and was based on a very complicated novel form. I made tremendous study of the novel. I had never made any formal study of the story. I mean, I had never taken any courses in creative writing except one from Tony Boucher, but I really studied the novel. I studied the French realistic novel, the Russian novel. I studied especially the products of the French Department of Tokyo University after the war. The Japanese students, they were writing very interesting novels. I read all of those that I could; they were more contemporary, and they updated the French realistic novel, and when I sent it off, it was based on a very sturdy complex structured form, which I have continued to use, a very intricate form, which, you know– have you read any of my novels?

James Holmes: Yeah.

Philip K. Dick: Would you say that the structure is pretty complicated?

James Holmes: For Solar Lottery, fairly, yeah.

Philip K. Dick: I beg your pardon.

James Holmes: What?

Philip K. Dick: For Solar Lottery?

James Holmes: Yeah, some of them, yeah.

Philip K. Dick: Well, Solar Lottery, for a first novel, is a pretty, you know, elaborate– you compare that to say to one of Ron Goulart’s novels. I mean, now he’s a guy– I went in to Tony Boucher’s writing class in 1951 with Ron Goulart. Now, Ron Goulart is making the transition to the novel after all this time, and I’m not gonna single him out– Let’s say that, you know, I think I have been successful as a novel writer not because I’m a better writer than some of these other people, but because before I began to send off novels, I had, you know, thoroughly studied the novel form and had a novel structure.

James Holmes: You do this all on your own? Did you go to college?

Continued in:

Part 5 Philip K Dick 1971 Interview