Part 13 Philip K Dick 1971 Interview

James Holmes: If you could be anyone in history, who would you be?

Philip K Dick: As little as possible, I’d like to go in and out of history in such a way that I did not get noticed, because that is what the Nazi’s called de stille imlande and that was the people that objected but they could never pin them down because they couldn’t find them and that’s what it means translated. The people who are silent throughout the country and this was the only way you could object in a state like the National Socialist state. With the death penalty, if you lined your garbage pail with something that turned out to maybe have a picture of Hitler on it, and they all did, so that was it, and yet there was this stille imlande and they could never get them all because the people made no sound, showed no characteristics, and somehow they undermined the regime in some subtle way. How could you draw up a document, an arrest document, you had no name, no address, nothing on them, and they were ready to arrest them all, and they never could find them and this is the way I think you should enter history and get out, invisible. They’re still looking for them, they went to Argentina and changed their names, they’re now hokeying up all those funky cars they’re building in Argentina. Sabotage is what it’s called, which means literally throwing your wooden shoes into the assembly line. What was it called in French, [sabot-wooden shoes made from a single block of wood], the wooden things, once they fell into the machinery, you couldn’t get the machinery turning for days, it slowed down to a crawl, things came off the assembly line, but it took longer. You could never pin down who did it because everybody’s shoes were identical. The mass man,

James Holmes: What do you think of when you read science fiction.

Philip K Dick: I don’t know, when I read it, it’s in translation and it loses something I guess, because it never strikes me as very good, just full of all kinds of poetic imagery which to me is out of place in prose. Like, can you tell me about it, maybe you could enlighten me about the new wave stuff.

James Holmes: I know I can’t.

Philip K Dick: Have you read any of it?

James Holmes: Well I don’t know, I’ve been trying to figure out what it is.

Philip K Dick: Is that Ted Carnells stuff?

James Holmes: I think it’s gonna be people like J G Ballard.

Philip K Dick: Oh yea, the drown world subject.

James Holmes: Yeah.

Philip K Dick: Did you read any of his stuff? Was it any good?

James Holmes: Yea, it was enjoyable, he has some good ideas.

Philip K Dick: What did you like it for you, for instance.

James Holmes: For instance, oh purely crystalline worlds, you know.

Philip K Dick: What goes on in them?

James Holmes: Not much.

Philip K Dick: A dull Saturday night. Reminds me of a Hal Clement called Mission of Gravity, it was a serial in Astounding, in the second installment, the preamble, or synopsis, began this way. For the first time in the history of man it became possible to measure a three gravitational field. I thought what a dramatic premise for a human life, man. What pathos, what tragedy, three gravities. So I asked somebody what the book was like because I couldn’t read it, he says they built this little airplane and they could only fly 5 feet, and I said why, because of the three gravities, and then he went on about the 3 gravities, pulled out a slide rule, measured me to see how far I’d fly. That’s the way Ballard struck me, because I’ve got all of Ballard kicking around here and I tried to read it, and it was sort of poetic, it was sort of poetic sterile stuff, sort of vivid, very vivid impotent stuff. Very, very vivid dull stuff.

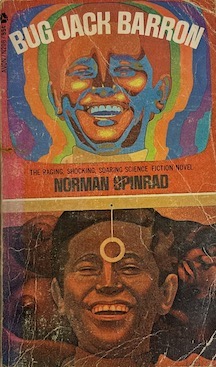

James Holmes: Some of Norman Spinrad’s stuff, like Bug Jack Barron, used to called new wave, sort of, I think Damon Knight called it second handedly trendy.

Philip K Dick: Norman said it was the dirtiest book ever written by him, he was going to get the most money he’d ever got in his life. Did he by the way?

James Holmes: I think he did.

Philip K Dick: I think he did too.

James Holmes: From what he said, his collection of short stories outsold it because it was sold by Doubleday science fiction.

Philip K Dick: Was it dirtier?

James Holmes: No it wasn’t dirtier.

Philip K Dick: I didn’t think Norman wrote dirty stuff, I’ve never been able to read a book, but don’t quote me about that because like I haven’t told Norman I couldn’t read Bug Jack Baron, but I had it around and I opened it, and it says this is the dirtiest book I’ve ever read, I’m going to buy all the copies that I can, mail them to people as Christmas presents. My check didn’t clear and I never got the presents. I don’t think that’s new wave, I think that’s an experimental model of the Henry Moore type, of the sort of, says an article by Judith Merrill one time in Fantasy and Science Fiction about new wave, which is about all I know about it. It was a contrast between the new wave stuff and what she called the old pulp pros and the old pulp pros were like Van Vogt, people like that, Stanley Weinbaum, the new wave stuff was whoever those guys are over there.

She mentioned me, I read paragraph after paragraph before finding about me, she said then there’s Phil Dick, I got ranked, she said now he stands between the two, he’s a lousy pulp writer like the old pros, he writes all kinds of unintelligible stuff like the new wave people, in addition his dialogue is all from the comic books. It goes like this, pow, zowy, gretta, it’s sure great in bed isn’t it, zam, wham, I said gosh that’s terrible. That’s the worst news I’ve ever heard. Then I read on, she said, therefore he’s the finest figure in the field, and gave reasons that made no sense. I got to thinking about this and I thought now here’s the quintessence of idiocy, my dialog is not like that, the new way stuff is probably beautiful, but like remembrance of things past has no future, is style and imagery without content, the old pros, like Van Vogt, Weinbaum, John W Campbell under the name Don A Stuart, were really very fine writers, nothing she says makes sense because it goes back to the whole thing between popular culture and the elite culture, the new wave is a kind of attempt to make into an elite thing the field that has always been a kind of popular or pulp thing, to give it prestige without quality, class without dignity, and readers who are more affluent and who like elegance, like her breast were like Florentine China man, 60% bone and glazed with the most beautiful lead glaze possible, melted down from byzantine mosaics. Tipped with gold, rose stained glass windows from Notre Dame. That would sell in England, I’ve got a low opinion of English science fiction.

James Holmes: I understand you’re more popular over in England and Europe than you are here.

Philip K Dick: You have a knack for words son. No they don’t like my stuff over there. That’s true.

James Holmes: But don’t you sell better over there?

Philip K Dick: No

James Holmes: Aren’t you more popular over there?

Philip K Dick: I don’t know, I’ve never been over there. I get letters from some writers over there, John Brunner for instance who I know very well comes to see me about every 18 months, which is when he renews his prescription for earth and novid [?] for his girlfriend, his wife, says that he likes my stuff. He did a big article of my stuff in France, which I can’t read which says I’m very good he says. Outside of John Brunner I don’t think I am liked at all over there. Ted Carnell doesn’t like my stuff at all.

James Holmes: There are fan people over there, but they don’t buy all your books.

Philip K Dick: Nobody buys my books over there.

James Holmes: Really?

Philip K Dick: No, they did for awhile.

James Holmes: What happened?

Philip K Dick: I don’t know some terrible calamity must have set in. I was published by the largest publisher over there, and my agent said that’s your publisher Phil and then all of a sudden they went and bought back every copy of one of my books that had been distributed, and then a great silence fell over England and they never bought anything again.

James Holmes: Which book did they buy back.

Philip K Dick: I’m not going to say.

James Holmes: come on.

Philip K Dick: They bought the title back and they erased my memory banks. No they’d used a different title, anyway I was never really popular after that point. What did I say in that book do you suppose that would turn off a whole country?

James Holmes: Well, maybe I can read it.

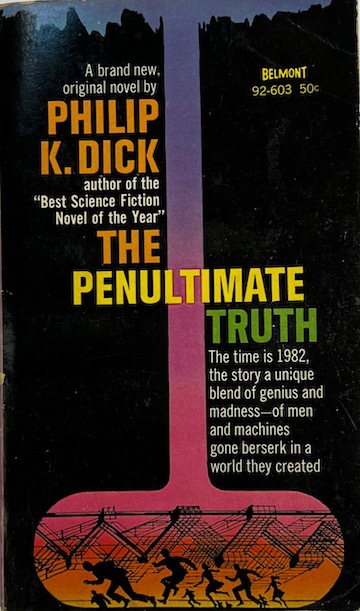

Philip K Dick: A Penultimate Truth

James Holmes: You didn’t say anything.

Philip K Dick: Maybe that’s what happened, that’s all that money and understanding. I sort of liked that book though.

James Holmes: I read it.

Philip K Dick: Do you remember anything about it?

James Holmes: Yea, I remember the title because I didn’t know what Penultimate meant.

Philip K Dick: I didn’t use that title, the publisher put that on and when I received the book I said what does penultimate mean. Turns out it means the next last right?

James Holmes: Right.

Philip K Dick: I don’t see how that refers to the book. I thought that was the ultimate truth I was putting down. That was my one attempt to tell what I thought was the ultimate truth, and it backfired, I ceased to be popular in England. I think I said that the Torreys were all homosexuals or something, I don’t know. I know I said something really bad because the German edition was translated into Braille and for those whose mothers had suffered from Rubella during their pregnancy. and distributed to the experimental labs so it must have been really awful.

James Holmes: Who do you think are the leading science fiction writers now?

Continued in:

Part 14 Philip K Dick 1971 Interview