Part 4 Philip K Dick 1971 Interview

James Holmes: You do this all on your own? Did you go to college?

Philip K. Dick: I went to the University of California for a while, yeah, but not at that point; before that, and I didn’t stay really long.

James Holmes: Yeah, and that wasn’t in English or creative writing?

Philip K. Dick: Heck no.

James Holmes: What was that in, just out of curiosity?

Philip K. Dick: Philosophy, the trashy stuff, of no use whatsoever. I got interested in Yeats and Euripides, though, while wandering around waiting for my philosophy books to be available at the library, so it wasn’t all a waste.

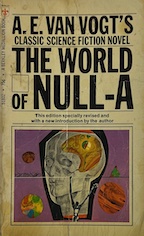

James Holmes: There’s a strong similarity between World of Null-A and Solar Lottery. I was wondering if you knew. Have you ever read World of Null-A?

Philip K. Dick: Yes, I have.

James Holmes: Yours is much better, I might add.

Philip K. Dick: That’s not my opinion.

James Holmes: I didn’t– That’s not–

Philip K. Dick: I hope that’s not Van Vogt’s opinion either.

James Holmes: Really?

Philip K. Dick: Yeah, because I think– No, now, like, you know, I sort of glossed over that. I read World of Null-A when it came out as a magazine serial in Astounding in the 40’s, and I thought that was a terrific novel, and when it came out in book form by Simon and Schuster later on, I bought that and it was different, by the way, than the magazine version.

James Holmes: Oh, it was?

Philip K. Dick: Yes, and I studied the changes that he had made, and I thought that was– first of all, I thought Van Vogt was a really great writer, I still do.

James Holmes: Really?

Philip K. Dick: Yes, a really great writer, and he was really my ideal. When I grew up in the 30’s, that’s when Van Vogt started publishing about 1939, I think his first story came out, and I started reading science fiction in 41, so he was publishing just about the time I started reading it, and he was my ideal as a writer. I mean, when I read– I couldn’t even figure out a recruiting station and some of that, I mean, he just lost me, but I say he’s really great because they were really great.

James Holmes: laughter] Yeah.

Philip K. Dick: And, they were great then, remember though. They were– I won’t put him put him down now, but let’s say at that time in 1941 and 2 and 3, because he wrote through the war– he was still writing during the war then, World of Null-A in 45, which I thought was great. So, anyway, I met Van Vogt in 1954, yeah, at the convention in San Francisco, and I didn’t anymore expect to meet Van Vogt than I expected, you know, to meet Chaucer. You know, I would have been just as surprised if Chaucer had come through the room, and I would have spoken to him, too, and I said, “Mr. Van Vogt, sir, your majesty,” and he said, “Are you the guy that’s got my pants, or is that somebody else?” I says, “No, I’m an ardent fan of yours,” and I told him who I was. I had already published so much of stories, and he says, “Gosh,” and he was really great. I mean, he looked at me like I really existed, and I said, “Mr. Van Vogt, I have read all of your stuff,” which was true, and “I think it’s really great, but I cannot fathom how your plots develop. I cannot understand the linkage that connects the progressions within your plot. Could you explain it to me?” He says, “Well, Phil, what happens is, I start with one plot, then it all peters out and goes nowhere and is no good, and then I think of an entirely new plot and work on that, and that peters out too, and then I try another one, and then I finally give up when I get the word rate right,” and I says, “Is that how it’s done,” and he says, “Well, that’s how I do it, and there’s the guy that’s got my pants,” and then he went off, and I thought, no, you know, he didn’t have to cop out to that. I mean, he could have put on a big pretentious response, you know, in line with my sincere but pretentious question, you know, and pontificated at great length, and you know, shuck me back and fulfilled himself, you know, as a mystic idol giving me what I wanted, you know? Instead, he told me what he believed to be the literal truth. It was not a put down on himself. It was not cynical. It was what a writer would tell another writer. It was candid. It was– I mean, I see that now. At the time, all I thought was, you know, the thing for me to do is just study his stuff and work out a theme or plot that does not break down partly, you know, through the thing, or take a number of themes as he does and join them together so they do function as an integrated whole and not have it break, because then I went back to World of Null-A and I can see where it did break down, and he did start really from the start again, you know, as if the first part hadn’t been there, so I thought if we could link these separate plot strands into one, I wouldn’t say successful Van Vogt novel; I would say we could enlarge it and make stronger, you know, what Van Vogt has been doing, and that’s what I tried to do in Solar Lottery was do what he had done, but make the different plot elements as he thought of them, something that I worked out in advance, that I didn’t start one and then drop it, but I had them all in my mind and deliberately construct them in sequence and integrate them. That’s what I tried to do with Solar Lottery, and this is something that I think I did actually.

James Holmes: I thought you did fairly well.

Philip K. Dick: Sold 298,000 copies, too

James Holmes: Is it still in print? I mean, is it still being–

Philip K. Dick: Yes, it is.

James Holmes: So, you’re probably gonna sell more.

Philip K. Dick: I saw it down at Mill Valley at the Greyhound Bus Station the other day.

James Holmes: You seem to have abandoned, though–

Philip K. Dick: I didn’t have enough money to buy them.

James Holmes: Van Vogt has a very sweeping kind of, you know, trying to encompass all of space; well not, you know, as much a space as he can handle with all these vast vistas, but after Solar Lottery, at least of the ones that I’ve read, you’ve kind of brought it back to earth and contented yourself mostly with, you know, with people and, you know, more social situations that are almost satires on current political, you know, or social situations that we’re in.

Philip K. Dick: Well, that’s not really true anymore, I mean, about my stuff. I don’t know how candid I should be. If I’m as candid as he was, I might not get the

enthusiastic response which he got from me because, like the fact of the matter is, I did the social satire stuff, which is not really social satire so much as anti-utopian type of thing, you know, where we got tired of the utopian novel, well they got tired before I came along, but like Darkness at Noon of Koestler and things like Huxley in a Brave New World, not to mention 1984, or anti-utopian novels which are reactions against the utopian novels, which I guess preceded them, but I was influenced by Pohl and Kornbluth’s stuff, which is very anti-utopian, and as far as satire, I can’t tell the difference. I mean, I have such a feeble grip on reality that satire, which presumably distorts and exaggerates and burlesques, you know, and somehow makes humorous by exaggeration of things, you know, which are not humorous in themselves, you know like Norman Spinrad’s story, what is that, the Carcinoma Angels or something, a funny cancer story, you know. Like, I don’t know the difference.

I mean, when I write this stuff, or wrote that stuff then, anti-utopian stuff, I wasn’t parroting or burlesquing reality. That’s the way I thought reality was. I mean, this is the way I experienced it. I mean, I find sinister large institutions funny, you know, because I have no choice. If I start facing reality, you know, I freak out. I mean, especially that was true then, you know, because that was during the McCarthy period, and you guys are lucky man, because if you think it’s bad now, it was really bad then. I mean, people were killing themselves literally out of fear, you know, of the kind of thing that could be done to them in public during the McCarthy period. Not– Well, I was gonna say not the smallest fish like me, but this could be done to small fish, too. This was done to an awful lot of people. There was a tremendous amount of fear in the country. I mean, it was really a terror and a legitimate terror. I was too dumb to know the difference. I went right on writing the kind of left wing stuff, you know, the radical stuff that I believed in when I had gone to school. You know, I was really left wing, and I went right on writing that kind of stuff right into the McCarthy period, right on through, and right on out, and it just was the way I experienced these large sinister institutions as being sort of funny; I mean, funny in the sense that– The Kafka is not funny. I mean, it would be like the trial, you know, where they say “you’ve been arrested,” you know, and you say “what for,” and they say “well, we don’t know because the other guy’s got that document,” you know, that says what you’re being arrested for. In my story, they would have the wrong guy. You see, in other words, they would arrest the wrong guy for the crime, you know, as in they wouldn’t tell him what he did; they would have the wrong guy who hadn’t done what he didn’t do or did do, and it would get all screwed up. The sinister forces of the court would let a document expire before they served it on him, you know, and it would all– everything would break down, and people would say you’re satirizing Kafka, you know, you’re satirizing the star chamber, the inquisition, or Cromwell or something like that, and I would say, “Gosh, no.” You know, this is the way when I went to the concentration camp, you know, to be gassed to death, they accidentally sent me to the showers instead, you know, instead of the other way around. You know, saying here’s the shower, when you go in your gassed, you know. I went in and say, “I’m ready to be gassed,” and I was given a free shower. I mean, this is the way I would write it because this is the way I would experience it. That was the social satire period, so called, that I went through. That would be like The Man Who Japed where the guy goes into the automat and there’s a human head behind one of the little glass windows, and he decides to order that but he doesn’t have the right amount of money, and when he does get the right amount of money, it isn’t a human head at all, it’s made out of plaster and he feels gypped, but he takes it home anyway, that kind of– Then I got out of that and started writing a psychological thing, which began really with Eye in the Sky. Did you read Eye in the Sky?

James Holmes: No, I didn’t.

Philip K. Dick: You got 75 cents?

James Holmes: I can read it now.

Philip K. Dick: That was the beginning of my psychological world. The sound of snuff; the check I wrote for the snuff bounced snuff guy here on mic.

James Holmes: What kind of snuff is that called, just out of curiosity.

Continued in:

Part 6 Philip K Dick 1971 Interview